Living in the quickly growing space between book and video game resides the genre known as interactive fiction. Interactive fiction generally focuses on character interactions and story engagement through text-based commands or devices. Developers Aaron Reed and Jacob Garbe decided to utilize the video games category to announce their Kickstarter project Ice-Bound, which may not adequately describe the successfully funded project.

Users interact with an AI program called KRIS, a computer intelligence designed to mimic the consciousness of fictional and immensely popular writer Kristopher Holmquist with the specific goal of finishing a manuscript left uncompleted as a result of his death. Players read through fragments left over in notes by the author and create the rest of the story themselves by selecting different options made available at set points.

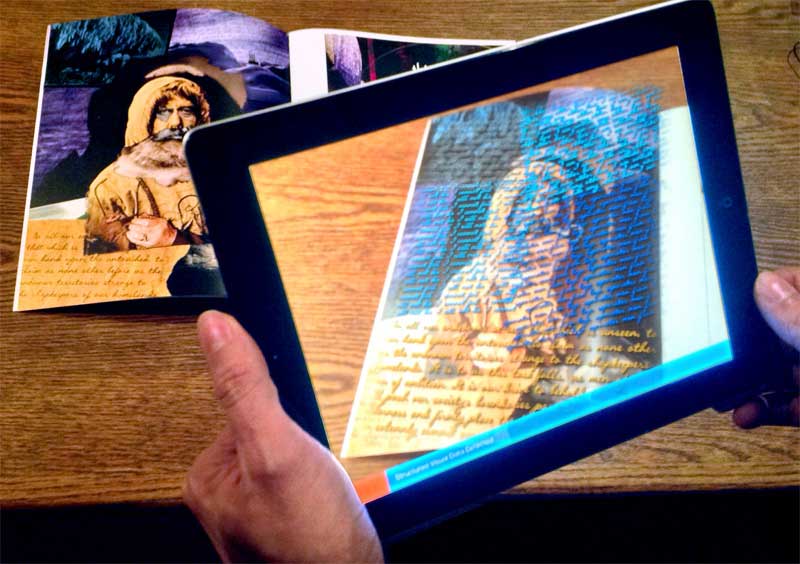

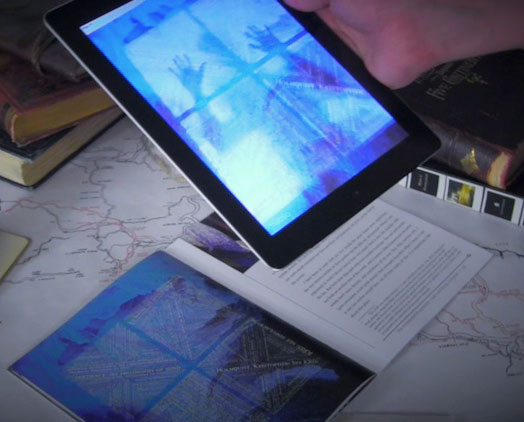

As the digital embodiment of the original author, KRIS must approve of the choices which is accomplished by showing support found in the physical Ice-Bound Compendium that is used in conjunction with the game. Using altered reality technology, KRIS will scan various pages players show it in support of their story decisions, while the AI slowly learns more about its’ creation and purpose.

Currently, Ice-Bound is set to be available for owners of the iPad 2 or newer as well as Windows PC’s equipped with webcams. According to their Kickstarter a MAC OS port as well as Android tablet functionality is planned but not guaranteed.

This unique fusion of game and narrative construction warranted further investigation which led us to sit down with developer Aaron Reed to learn more about developing for interactive fiction, and the functionality of Ice-Bound.

Jesse Tannous: Describe the pacing of this experience will there be chapters or clear stopping points? How were those implemented as to not break the immersion of Ice-Bound?

Aaron Reed: The story’s divided up into eight chapters, each one corresponding to a deeper level of Carina Station. Each level tells a self-contained story of people who lived at the station at a particular time… the deeper levels are older, and thus farther back in history. In the later levels, the stories start threading together a little more complexly (but I’ve already said too much).

The breaking serves a similar purpose to chapters in a book: giving you a place to stop for a while if you like and resume later without being too lost, and a sense of progression through the narrative.

JT: You mention how the AI program can react differently to certain prompts found within the Ice-Bound Compendium. Will players know beforehand what prompts will result in certain responses or will that be something that they simply have to figure out over the course of playing?

AR: A little of each. When you’ve arranged a certain story the way you like it, KRIS (the AI simulation of Ice-Bound’s original author) will ask you to find some evidence in the printed Ice-Bound Compendium that your version of the story is correct. He’ll do this by looking at a set of “themes” which each potential ending fragment is tagged with. Each of the pages in the printed book are also tagged with themes. You can’t see those themes directly, but the content of the page helps you understand what they are. Showing KRIS a page that has a theme in common with your ending will convince him that your version of the story is appropriate. An important facet of this is that there isn’t a single right answer: there are enough pages (80) and ending fragments (er, hundreds?) that you can use surprising pages to resolve endings in ways we as the creators didn’t specifically think of in advance.

The catch, though, is that KRIS also picks up other information from the pages you show him: things about his past or his digital rebirth that his creators would rather he didn’t know. Showing him a certain page might get the ending you want, but might also give KRIS the last piece of evidence he needed to understand a secret from his past or something about his ultimate fate. So the choice as player of what page to show him is complicated: how much do you want to reveal to him, and when?

JT: Depending on player choices will different players be exposed to completely different stories or will their choices simply effect details within the same core narrative?

AR: The individual stories of each chapter can change quite dramatically based on player choices, even to the point of being in different genres. Part of the joy of the system is exploring how seemingly minor changes can have drastic effects on the whole narrative. Giving a character a drinking problem might unlock a whole set of events and endings that weren’t there when she was afraid of the dark, instead.

You’re exploring these stories in the larger context of your ongoing relationship with the AI writer, KRIS. His story follows more of a pre-set path, although many of the specifics can still vary quite a bit (his mood, and what information he’s learned about himself, can trigger various scenes and lead to a number of possible endings for him).

JT: Since you and your partner have been involved with the interactive fiction (IF) genre for quite some time can you explain how the genre is doing? Is it growing and innovating or is it suffering from stagnation and lack of mass appeal? If the latter what can be done to change that?

AR: IF is actually in the midst of an extraordinary renaissance right now. Over the past few years, a combination of the rise of mobile devices that make casual reading of digital texts easier than ever, and a proliferation of new tools for writing this kind of content, has really created a perfect storm for a rebirth of digital text. I can’t even keep track of all the new systems and communities flourishing right now: StoryNexus, Inklewriter, ChoiceScript, Twine, and Versu, to name a few, alongside older tools like Quest and Inform. As far as the games, you’ve got stories driven by complex simulations of social convention, like Blood and Laurels from Emily Short; you’ve got the brilliant writing and experiments in form by people like porpentine in “their angelical understanding”; you have the success on Steam of interactive narratives like Christine Love’s Analog: A Hate Story, Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest, or Zachary Sergi’s Heroes Rise. And I guess the fact that our own text-driven game just won IndieCade’s Story award maybe counts for something too.

In short, there’s an explosion of interactive fiction right now, and it’s amazing to be watching it evolve.

JT: What would you recommend for someone interested in breaking into development for this particular genre?

AR: The barrier of entry is refreshingly low compared to many other game genres. Twine is a really popular tool right now for creating link-based fictions, and ChoiceScript is another easy system for making choice-based narratives that can track state over time. Versu and Inform 7 are more complex systems for telling stories that involve more sophisticated simulations of people, places, and things. One of our Kickstarter stretch goals is to open source the narrative engine behind Ice-Bound, so that might soon be a potential option, too. I think the biggest advice I would say is start playing what’s out there, join the conversations online, start making work and releasing it. You don’t need art assets or 3D modelers or an expensive engine. You just need words.

Ice-Bound certainly promises to be a very different type of game, but seems to promise an interactive experience that allows for creativity and individual experiences.

Jesse is a reporter first who just happens to love video games and enjoys writing video game related articles and interviewing industry professionals.